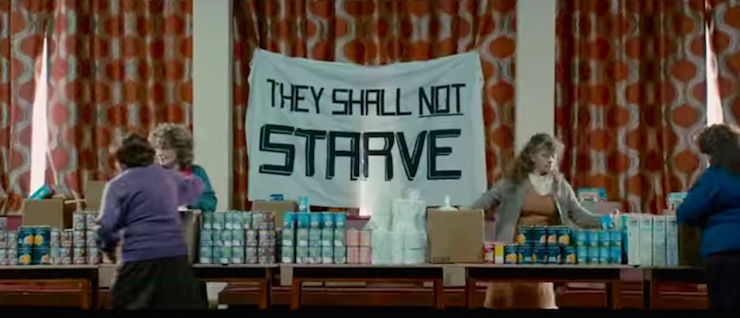

Several weeks ago, I watched Pride, a fascinating political drama documenting the true story of a few London-based gay rights campaigners who in 1984 decided to support some beleaguered striking Welsh coal miners. It’s a genuinely heartwarming story about political solidarity. If you have a chance to see Pride, you should.

Several weeks ago, I watched Pride, a fascinating political drama documenting the true story of a few London-based gay rights campaigners who in 1984 decided to support some beleaguered striking Welsh coal miners. It’s a genuinely heartwarming story about political solidarity. If you have a chance to see Pride, you should.

The coal-miners’ strike was in opposition to Margaret Thatcher’s decision to close several coal-mining pits. Pride does a great job demonstrating the sheer emotional impact of that industrial and political dispute. For coal mining communities, the strike was a desperate struggle against an existential threat. The movie is made particularly sad by the fact that many viewers, with the benefit of posterity, will know that the coal miners lost their battle and the mines closed anyway. There are those who would tell you that many parts of Britain have never recovered from the closure of those mines.

But wait…aren’t coal mines a bad thing? Certainly they are for anybody concerned about the climate. Whatever other innovations and efficiencies we come up with, the bottom line is that we have to leave most of our fossil fuels in the ground. If you look it in that light, then Margaret Thatcher actually did us all a favour.

This is an uncomfortable position that extends well beyond film criticism. Whether we’re talking about coal miners in the 1980s or today’s Albertan tar sands workers, the simple fact is that climate action will hurt them. Not everybody who will be inconvenienced by climate action is an oil magnate; saving the planet will have collateral damage. But, of course, if we fail to act, then climate change will hurt everybody, including the workers.

Much of the wider left-wing will swiftly desert the climate cause if it cannot be squared with the livelihoods of the working class.

This is a strategic problem as well as an ethical one. Not only labour unions, but also much of the wider left-wing will swiftly desert the climate cause if it cannot be squared with the livelihoods of the working class. There’s a reason the word “jobs” is such a potent rhetorical weapon when used by vested interests opposed to climate action. One good way to counter this is with the promise of green jobs. But while it is indeed true that the green economy will need lots of wind turbine technicians and electric car battery factories, that doesn’t do much in the short-term for people whose primary skill is mining coal or drilling for oil. Even if those people can eventually find green jobs, they will still need to eat while they retrain. So the tension between jobs and the climate persists. We need a way to square this circle, or we will lose.

I’d like to propose a potential way to do that: Environmentalists should embrace the sustainability benefits of a guaranteed basic income. The idea is very simple: Everybody receives an unconditional sum from the government that is enough to cover basic living expenses. The only case in which this could ever be taken away is if somebody earns enough money to make it no longer necessary. A basic income would replace welfare, food stamps, unemployment insurance, social security and a whole range of other programs, thereby saving administrative costs.

The best argument for a basic income at the moment is founded on the automation crisis, rather than the climate crisis. Analysts expect that self-driving cars will be dominant on the roads by the 2030s, and that means self-driving trucks, taxis, delivery vehicles and forklifts. That, in turn, means a lot of people out of work. Combine that with progress in other fields of automation such as 3D printing and robotics, and suddenly it looks like a lot of jobs are going to disappear. YouTuber CGP Grey explains the coming automation crisis in an excellent video titled “Humans need not apply.” But if there are going to be far fewer jobs for which humans can apply, then maybe we need to rethink the idea of productive labour as a prerequisite for survival.

Any economic structure which removes the financial incentive for ordinary people to destroy the planet is a good thing.

The idea has received support from some surprising places, including archconservative economist Milton Friedman. And basic income experiments have already been tried in London, Manitoba and New York City among other places, with good results.

Despite the range of economic, ethical and social justice arguments being made for a basic income, environmentalists seem to have largely missed the idea’s implications for sustainability. This should change. A basic income would remove the tension between saving the planet and supporting the working classes. Any economic structure which removes the financial incentive for ordinary people to destroy the planet is a good thing. People who depend on their environmentally destructive jobs for survival can hardly be blamed for dismissing the concerns of environmentalists. A basic income would give them the economic freedom to take climate change seriously. If the miners in Pride could have relied on enough money to remain in their community even after the pits closed, then the story might not have been so sad.

Cameron Roberts is a Canadian PhD student studying the cultural history of transportation technology at the University of Manchester. He blogs about science, technology and society at Where’s My Jetpack.