“What part will you play?” (p. 171) is the question Michael Blencowe puts to the reader while he searches for what remains of some of Earth’s extinct species. Gone tells the story of eleven of the Earth’s fascinating, and now extinct, creatures, from the Xerces Blue to the Schomburgk’s Deer. Blencowe brings us along on his pilgrimage to the archives, museums, and last location sightings of his beloved extinct creatures. He traverses from the United Kingdom, to Thailand, to California, and back again, and we are brought along for the ride.

Gone is a memoir. It is a memoir that reflects back on Blenowe’s own lifetime, but it is also a journey back through the history and the life of species now lost. In his quest for these extinct species and the places they lived, Blencowe relates tales of the early explorations and sightings of these species, alongside stories of the peoples and societies, sailors and explorers, who first encountered them. We get to know the character of these species as well as that of those who were discovering and writing about them: the gentle and loving nature of Steller’s sea cow as well as the generosity and grit of the scientist Steller himself. This expansive exploration into the life and death of some of Earth’s most fascinating creatures is peppered throughout with humorous anecdotes of Blencowe’s own life, which add a touch of levity to the heavy subject of loss.

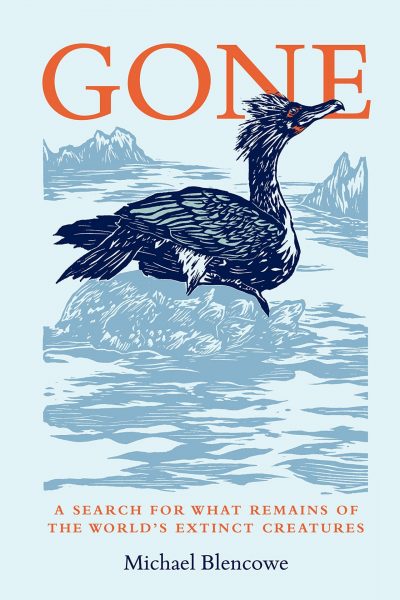

The cause that Blencowe sights for the extinction of these species is human interaction with them – overfishing, overhunting, introduction of invasive species as predators – making the overarching theme of this book a sobering one. Interestingly, there is not much focus on the loss of habitat and the part that it plays in species decline and loss of biodiversity. Through retelling the evolutionary process of the trusting upland moas and the life of Lonesome George, the last of the Pinta Island tortoises, Blencowe challenges humans to consider the effect that we have on non-human species, in their everyday lives, and ultimately, on their very existence. He further argues that too often, this challenge is not taken up and the results can be devastating. Because of this, it is a difficult read at times, and Blencowe does not hold back. He is quick to condemn practices and behaviour that he considers to be detrimental to the non-human world. However, his story telling really, as he hopes, helps to keep these extinct creatures “alive a little longer” (p. 181), to say nothing of the beautiful artwork throughout. True to his literary style, Blencowe leaves us with a comical and unsettling picture of hope – floating on his stomach on an inflatable crocodile while searching for a sea anemone in a muddy lagoon with a faltering flashlight – that, while dire, all may not be lost.

Anna Beresford is a PhD student in Social and Ecological Sustainability at the University of Waterloo. She is investigating the role of music and music cultures in developing resilient local communities and economies. In her down time, she enjoys kayaking, playing music, and having a good chat over a craft brew.