Breaking News

- 1 year ago

- WHERE THE WILDWAYS ARE

- 2 years ago

- They Call It Worm. They Call It Lame. That’s Not Its Name.

- 2 years ago

- Climate of Change Episode 4: ‘Rewiring the Future’ Review

- 2 years ago

- The Playbook for Progress Homepage

- 2 years ago

- Climate of Change Episode 3: “Faith, Hope, and Electricity” – A Review

Solid Grounding

How IQ – or Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, meaning traditional knowledge – is contributing to a more holistic conservation model with the Aviqtuuq IPCA in Nunavut

Written by: Mélanie Ritchot

Giving his son his first bite of country meat — or traditional Inuit food — is a moment Tad Tulurialik, a hunter from Taloyoak, a town of just over 1,000 people in Nunavut, can still picture.

“I remember my son crawling and sitting up on his own…I had some frozen caribou and I cut him a few slices and that first bite he had, his face just lit up,” said Tulurialik.

Now, his son is nearly one-and-a-half years old and eats country foods like caribou and frozen Arctic char.

Tulurialik can harvest traditional meat for his family, but for others who don’t have the proper equipment to go out on the land, the traditional knowledge, or the money to buy it in the stores, country food isn’t as accessible.

The community’s solution to this is twofold; a team of hunters and partner organizations like ArctiConnexion and World Wildlife Fund Canada are working to get a new country meat processing facility up and running in the next year. But, for the project to be sustainable, the wildlife populations themselves must stay healthy.

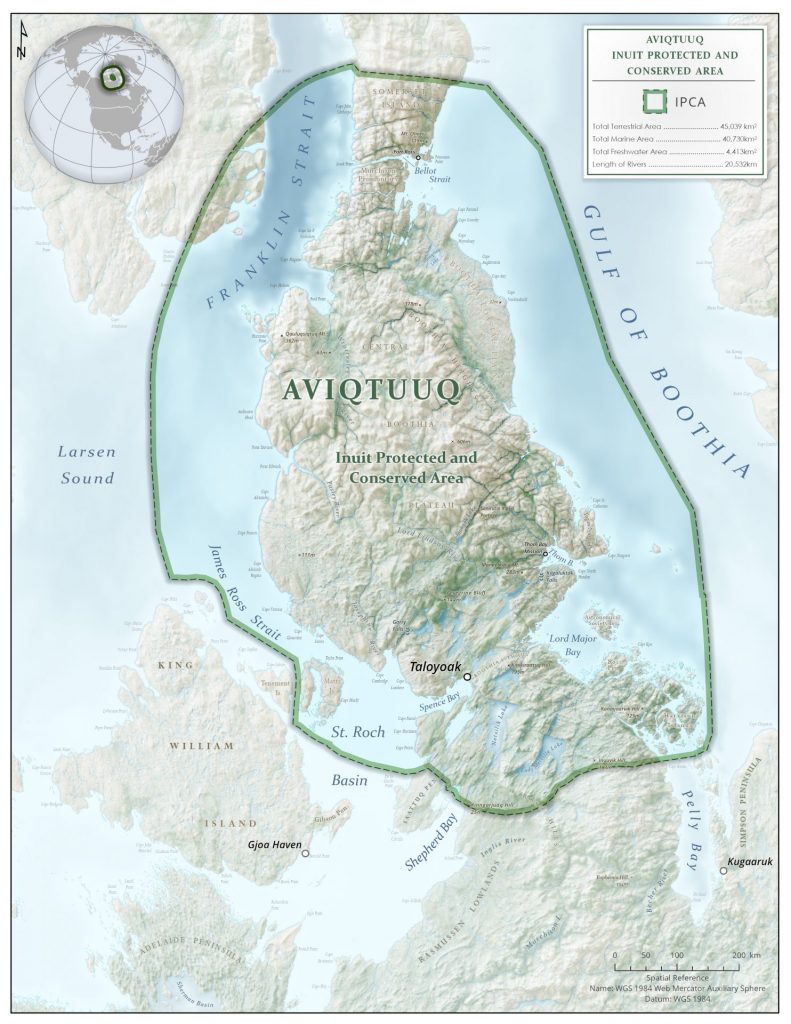

To ensure long-term conservation of the land, rivers and ocean — and therefore, the animals Inuit depend on — the group is working to get a 90,000-square km area on Boothia Peninsula (known as Aviqtuuq in Inuktitut) recognized as an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA). This would be the first IPCA in Nunavut and would put Inuit at the forefront as primary decision-makers for what is done with the land.

In 2015, Canada committed through Aichi Target 11 of the UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity to conserve 17 per cent of land and inland water area and 10 per cent of coastal and marine area by 2020. The federal government failed to meet the terrestrial goal. However, they surpassed the marine target thanks to Tuvaijuittuq, a Germany-sized interim marine protected area in the polar region that WWF-Canada dubbed the Last Ice Area because it’s where scientists project sea ice will persist the longest.

A report published in Environmental Science and Policy in 2019, found most countries aren’t meeting land protection goals but that Indigenous-led conservation areas could help remedy this.

It found Indigenous-led conservation areas in Brazil, Australia and Canada foster more biodiversity and have kept more threatened species healthy than non-protected areas in the same countries.

In many Crown-protected areas in Canada, conservation is achieved by restricting human activities and limiting access, whereas within Indigenous beliefs, the health of the land and of humans cannot be separated. The survival of wildlife and of humans are closely linked.

Instead of making entire areas off-limits for people, IPCAs can use a zoning method. For example, some parts of the IPCA could have restricted access, while others allow tourism or other activities. None of it is set in stone and Inuit could also decide to allow development on the land. IPCAs are meant to represent a long-term commitment to protection, provide opportunities for Indigenous peoples to reconnect to the land, and foster economies based on conservation.

Tulurialik is part of a project called Niqihaqut — “our food” in Inuktitut — which aims to tackle the lack of access to healthy, culturally relevant foods for Inuit in Taloyoak while also forming the basis for the IPCA’s management plan. It was just awarded a $451,000 Arctic Inspiration Prize to help get it off the ground.

When possible, hunters in Taloyoak distribute meat to families and elders in their communities, but most still rely on the local store for groceries. At the going prices, country meats aren’t regular purchases for most and they aren’t always in stock.

Tulurialik said at the store in Taloyoak, one fillet of Arctic char costs about $80. A small bag of caribou meat goes for about $50. Items found in southern grocery stores are also more expensive in Taloyoak and across Nunavut, as almost everything needs to be flown in.

Niqihaqut will include a new meat-processing facility. It will not only make country food affordable and readily available to residents but create new learning opportunities for youth and new jobs, resulting in a country food-driven economy.

While Niqihaqut will make country food more accessible, caribou, seal, whale, muskox and other wildlife populations must remain healthy for generations to come to make regular, sustainable harvests possible. This is where the IPCA comes in.

Jimmy Oleekatalik, the president of the Hunters and Trapper Association, is spearheading the IPCA project (called Aviqtuuq), and said it has been in the back of his mind since the 70s, when his community had to fight against a proposed pipeline that would interfere with animal migration routes.

“Since then, the elders have been wanting to protect Boothia Peninsula…but it never really got anywhere,” said Oleekatalik.

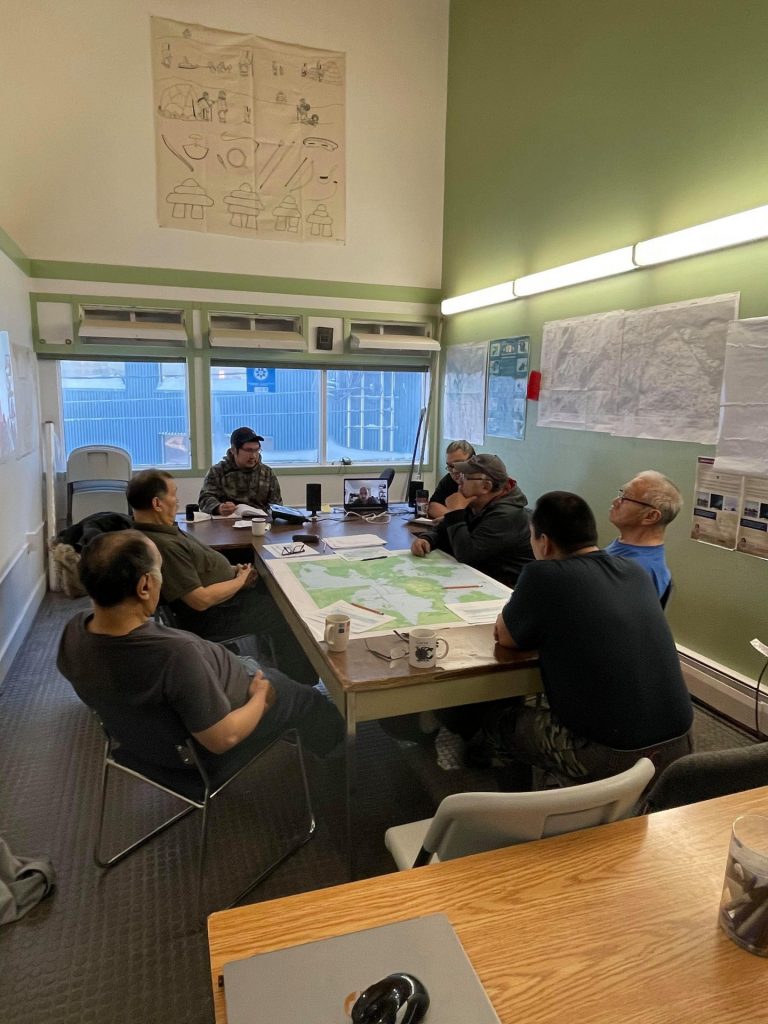

In 2016, Oleekatalik circled the proposed conservation area on a map with a marker, and sent it to the Nunavut Planning Commission, explaining what the community wanted.

“We want [wildlife populations], especially the caribou herd, to be healthy for generations…without any disturbance from mining or exploration,” he said.

The caribou herd near Taloyoak is currently healthy, but the community has seen populations dwindle in other unprotected areas.

“Caribou is our main diet and the whole caribou is very useful to us traditionally,” said Oleektalik.

Parkas and other winter clothes are commonly made from caribou skins, as well as traditional drums. Inuit use every part of animals they harvest — such as seals, whales and muskox — with purpose. They are not hunted for sport.

Mining and exploration are a threat to land and biodiversity that has come up time and again across Nunavut communities. Currently, a resource extraction company already has a prospecting tender for an area of land the IPCA aims to protect (it’s in the early stages and has been stalled by the Covid-19 pandemic).

Mining activity risks contaminating the land and waters and can also interrupt animals’ migration patterns, many of which pass by Taloyoak. There is also the risk of an oil spill which is much more difficult to clean up in Arctic conditions.

Oleekatalik said global warming is another cause for concern and he has seen the effects of climate change first-hand over the years. From warming seasons, shorter winters and more humidity, the land is different than he remembers as a child.

“We’ve relied on the ice to go from place to place for many generations,” he said. The ice is no longer as reliable, but Inuit are still able to follow safe routes based on elders’ knowledge,” said Oleekatalik.

“Caribou are at risk, the muskox are at risk…humans are at risk,” Oleekatalik said.

When Oleekatalik first brought his map and proposal to the planning commission, there wasn’t much of a reaction, he said.

Brandon Laforest, a senior Arctic specialist with WWF-Canada, said Oleekatalik approached him about three-and-a-half years ago, saying “we’ve been trying to get going on this protected area…we can’t get anyone to listen to us.”

WWF-Canada helped the team “basically create the same submission,” Laforest said, including digitizing the map and adapting Oleekatalik’s work to meet the technical requirements of the planning commission, “which kind of highlights the colonial nature of these processes.”

They also helped connect the Aviqtuuq team with officials at Environment Canada and other government agencies. “We can use our platform to make people listen to [them],” Laforest said.

The project is now making headway, and Oleekatalik said he hopes to see the protected area realized in his lifetime. But there are still barriers, including a lack of legislation on IPCAs in Canada, Laforest explained, since it is an emerging tool.

After Canada committed to Target 11, an Indigenous Circle of Experts was formed to give recommendations on how to achieve it.

ICE’s report, released in 2018, states there are 55 different pieces of legislation for creating protected areas in Canada and there is no national legislation that recognizes voluntary conservation actions by Indigenous peoples.

Historically, parks and protected areas in Canada have not been centred around the well-being of nature, but around recreation.

“Indigenous peoples were understood as obstacles to the enjoyment of nature,” the report states, and “the most insidious impact of historical protected areas is the disconnect they fostered between Indigenous peoples and their territories.”

Michael Ferguson is the senior wildlife advisor with the Qikiqtaaluk Wildlife Board, who has worked with and learned from Inuit for over 20 years in his capacity as a scientist.

He said one of the main differences between Inuit conservation and a more science-based approach is the expansive environmental knowledge Inuit have passed down for generations.

Much of the science on the Arctic is poor quality because of short study periods and areas; it spans 40 to 50 years at most, he said.

IQ — or Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, meaning traditional knowledge — goes back hundreds of years and is typically passed down through oral storytelling by elders.

“So, when Inuit look at the environment and see a change, they have knowledge of past changes, what the causes of past changes were…they can put it into a much broader context than science can.”

“They understand the orders of magnitude of change that are present, while scientists count things.”

Ferguson has studied caribou in the North for years and said he has received predictions from Inuit about the herds’ health and migration patterns since starting to survey the species.

“I’ve strategically tested predictions Inuit have made about caribou that were looking 10, 20 years into the future…every one of those predictions came true.”

He explained how Inuit understand the fluctuations in caribou populations and when they will change or move areas.

When a more colonial approach might suggest limiting harvests to allow the population to grow, for example, Inuit hunters understand the cycles different species go through and when the land may need to rest to allow the lichen, which is caribou’s main food source, to regrow.

Without harvesting, caribou could also overgraze the lichen, causing other ripple effects.

“I have never heard elders say that these cycles should be modified or changed.”

“I’m not against scientists because I am a scientist,” said Ferguson. “It’s a huge bending of the mind from science to this sort of knowledge base, but that knowledge base is valid.”

Although Canada only met the marine portion of its 2020 Target 11 goal, the federal government has since raised the stakes by committing to protect 25 per cent of Canadian lands and waters by 2025 and 30 per cent by 2030.

An Aviqtuuq IPCA, which would be roughly half-terrestrial and half-marine, could provide a crucial opportunity to not only help hit those targets, but to do so through Indigenous-led conservation.

Mélanie Ritchot is a Métis journalist who grew up in Manitoba and now lives in Iqaluit, Nunavut. She is currently a reporter for Nunatsiaq News, a publication whose audience resides in the eastern Arctic, and writes long-form pieces about Indigenous art and environmental issues on the side.