Breaking News

- 1 year ago

- WHERE THE WILDWAYS ARE

- 2 years ago

- They Call It Worm. They Call It Lame. That’s Not Its Name.

- 2 years ago

- Climate of Change Episode 4: ‘Rewiring the Future’ Review

- 2 years ago

- The Playbook for Progress Homepage

- 2 years ago

- Climate of Change Episode 3: “Faith, Hope, and Electricity” – A Review

What Lies Beneath

Canada’s first carbon map will help us fight the climate and biodiversity crises

Written by: Siobhan Mullally

Nature is already working to mitigate climate change, so protecting it is one of our best defenses. That was the message from Canada’s minister of environment and climate change, Jonathan Wilkinson at the Leaders Summit on Climate’s Ministerial Session on Nature-Based Solutions this past Earth Day.

“We are in a somewhat unique position: Canada is a G-7 country that is both an industrial emitter and has some of the world’s largest carbon stocks in nature,” he said, adding that safeguarding carbon-rich ecosystems will be one of the most effective and lowest-cost nature-based solutions to climate change.

“Our climate goals depend on us addressing the full carbon cycle and protecting nature.”

But do we know whether we’re protecting the right areas? Namely, those that are richest in carbon and most important for wildlife? A new study by WWF-Canada and McMaster University is aiming to find out.

We know that nature-based solutions aim to enhance natural processes — carbon sequestration, nutrient cycling, riparian flood control — that regulate our climate and allow biodiversity to thrive ultimately, by protecting nature. But with Canada warming at twice the global rate — and three times the average in the Canadian Arctic — we’re seeing declining trends in species’ population levels.

The climate crisis and the biodiversity crisis are two of the most urgent, life-threatening issues we face today, and they’re inherently linked, driving one another forward. Nature-based solutions can address the complexities of both by protecting land that stores large amounts of carbon while at the same time safeguarding important wildlife habitat and ultimately slowing climate change.

And much of this carbon is found in our soils.

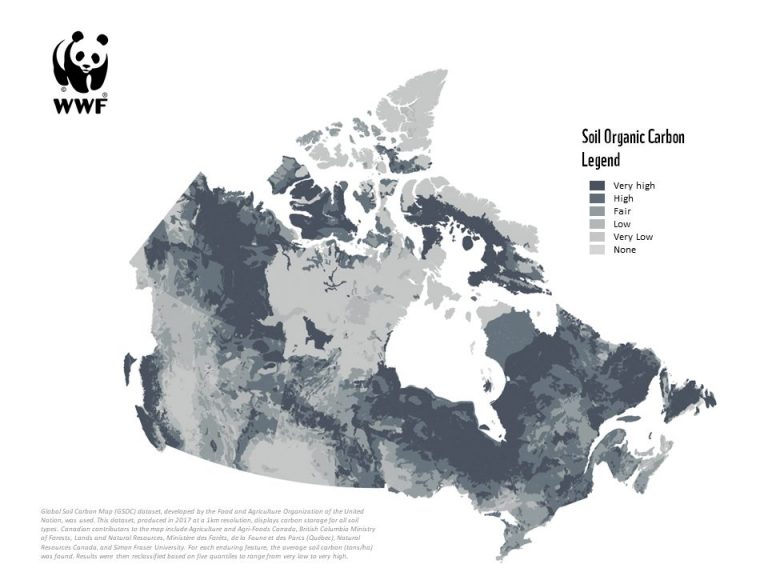

Soil Carbon in Canada

Canada is home to vast areas of carbon-rich ecosystems, and of these, peatlands are particularly unique — plants decompose slowly within these wetlands, and if left undisturbed, they store huge amounts of carbon beneath the Earth’s surface. Canada has among the world’s largest area of peatlands, spanning over 1.1 million square kilometres, which is almost 12 per cent of the total land area in Canada. The carbon stored in peatlands has accumulated and been reserved in the soil for likely hundreds to thousands of years. Carbon-rich hotspots in Canada have been identified in northern Ontario, coastal British Columbia, and an area roughly bordering Yukon and the Northwest Territories.

These regions play a significant role in mitigating climate change since they sequester and store carbon for long periods of time, leaving Canada with an enormous amount of accountability. If disturbed, catastrophic amounts of carbon could potentially be released. And the scary thing is, some people love to dig.

One key area for carbon in Canada is the Hudson and James Bay lowlands in northern Ontario, further explained by Jazmin Pirozek’s article “Returning to Muskeg”. This area is the traditional territory of seven First Nations that form the Mushkegowuk Council. It contains vast swaths of peatland and is also downstream from the Ring of Fire — a mineral-rich mining hotspot.

As development in the area rages onward and industries continue to shove their various extraction tools into the earth, the carbon in the ground is increasingly vulnerable to being released into the atmosphere, which would put climate change on the fast track. It is critical that we safeguard our carbon-rich lands and work toward fully understanding the potential implications of development on soil carbon, especially given that 77 percent of habitats with high density soil carbon in Canada are inadequately protected, if at all.

This is why WWF-Canada and researchers from McMaster University’s Remote Sensing Lab are joining forces to map out the stored carbon in Canada’s soils; to inform decision-making and improve our collective understanding of the potential impacts of development in carbon hotspots with respect to climate change.

Collaborative Carbon Mapping Project

The carbon mapping project was borne from a need for a National Carbon Map to show carbon deposits throughout Canada. Comprehensive soil carbon data is essential to identify and avoid major climatic threats. This particular knowledge gap presented an opportunity to protect biodiversity and slow climate change by advancing our understanding of where these carbon ecosystems are in Canada and how they behave.

“The goal of the project is to quantify and map the carbon stock in the soil in Canada. For soil, it’s the first map made at the national level. We have global maps, but this map is specific to Canadian environments — particularly, peatlands, a very important environment,” says Dr. Camile Söthe, post-doc fellow and key researcher from McMaster’s Remote Sensing Lab.

WWF-Canada also has ongoing collaborations with the Mushkegowuk Council regarding carbon stores. The Ring of Fire is a high-profile development area which attracts proposals frequently, so the conservation work is complex.

Development could jeopardize these vulnerable carbon-rich ecosystems, and without sufficient information in hand to accurately determine that the development would not harm wildlife or exacerbate climate change, nothing can move forward or be adequately protected. The apparent consensus from local groups, including the Mushkegowuk people, is that they do not want to see development occur until the potential threats are understood. The carbon map project is at the centre of this understanding.

Applications of the National Carbon Map

The purpose of the National Carbon Map is as a tool and resource to help inform and direct conservation efforts in a way that maximizes ecological benefits and protects carbon stores. At the same time, it would protect biodiversity and enhance the broad suite of benefits that communities derive from healthy ecosystems.

One critical use of the map will be to ensure that Canada stays on top of its international commitments to lower carbon emissions. By showing where the carbon hotspots are, we can direct climate action toward carbon sequestration and protecting the storage power of peatlands.

“In this case, we do believe the Hudson and James Bay lowlands — the peatlands there — are globally significant. I think this project provides a globally significant example of how we’re working together from the conservation community, led by Indigenous communities, and bringing the tools and resources to effectively protect, and follow the priorities of those Indigenous communities and what they want to do with their traditional lands,” says James Snider, VP of Science, Knowledge, and Innovation at WWF-Canada.

Moving Forward

“These maps will become the baseline, and we can start monitoring how these carbon reserves are affected when different natural or human disturbances occur. Then, it will help us to think of strategies to reduce carbon emissions and slow down climate change,” Dr. Söthe explained.

With the National Carbon Map currently under review for publication, the next step in the partnerships between WWF-Canada, McMaster University, and the Mushkegowuk Council is gathering additional on-the-ground data to support the map’s findings. A team of field data collectors have plans to take core samples and run tests to determine the carbon found in each area.

“We’re very much hoping that community members will be a part of the sampling. We’re in the midst now of doing the training for that in terms of making sure that we do have good participation from the communities,” Snider says.

The carbon stored in these peatlands will become increasingly important in the future. The creation of the National Carbon Map, as well as ongoing data collection, monitoring, and measuring of stored carbon, ensures that we maximize nature’s capacity to slow climate change by first and foremost understanding it, and then protecting it to keep carbon in the ground.

Siobhan Mullally is studying Environment, Resources and Sustainability (ERS) at the University of Waterloo while also minoring in English Language and Literature. As a writer and environmentalist, she is passionate about exploring environmental communications to inspire climate action. She is also a budding ecologist, researching climate change impacts on Arctic ecosystems in Labrador, Canada. In her free time, she enjoys spending time in nature and getting lost in her favourite novels.