Breaking News

- 1 year ago

- WHERE THE WILDWAYS ARE

- 2 years ago

- They Call It Worm. They Call It Lame. That’s Not Its Name.

- 2 years ago

- Climate of Change Episode 4: ‘Rewiring the Future’ Review

- 2 years ago

- The Playbook for Progress Homepage

- 2 years ago

- Climate of Change Episode 3: “Faith, Hope, and Electricity” – A Review

Course Correction

What the Shipping Industry needs to do to protect marine animals

Written by Alexandra Scaman

“We could potentially be watching these species walk toward the edge of extinction and we don’t have the information to know that it’s happening. We certainly don’t have the information to know how to stop it.”

Maritime shipping remains one of the cheapest ways to move larger quantities of goods such as fuel or pulpwood over long distances. As a result, global shipping traffic, as well as the size of container ships, have continued to grow over the years. According to the World Wildlife Fund, global ship traffic increased by 300% between 1992 and 2013 and continues to grow at a rate of 2-3% per year.

Canadians personally benefit from the shipping industry in ways we may not realize. A decline in commercial maritime shipping within Canada could equate to a 1.8% reduction in GDP (approximately $30 billion in 2016) and the loss of nearly 100,000 jobs.

Unfortunately, not everyone is benefiting.

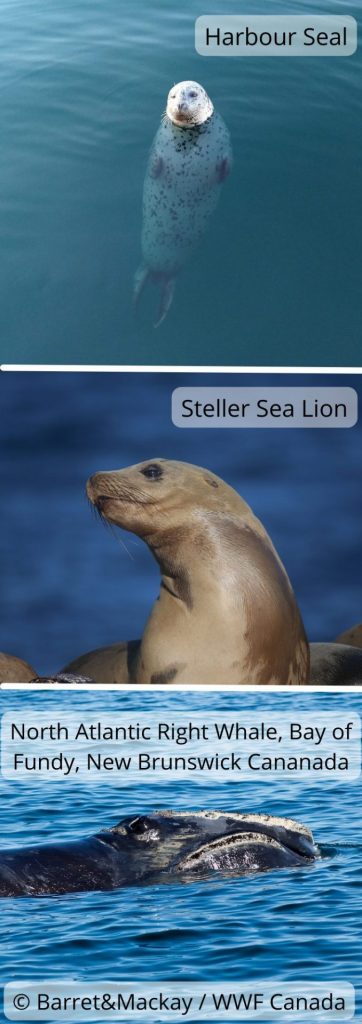

A plethora of direct and indirect environmental risks accompany maritime shipping. These include carbon dioxide emissions (shipping emits about 3% of the global total, around the same as aviation, and could reach 17% by 2050), transporting invasive species, increasing noise pollution, and an elevated risk of oil spills or collisions impacting marine fauna, such as whales, seals, or sea lions, to name just a few.

This is also an increasing concern in the Arctic as melting sea ice attracts more shipping traffic. In this sensitive polar region, underwater noise has more than doubled between 2013 and 2019 (and in some areas, like Barents Sea and Baffin Bay, it increased tenfold), oil spills are an even greater challenge to clean up, and threats to wildlife also threaten Inuit food security. No wonder there have been protests over the controversial proposal to double the output of Baffinland’s Mary River iron mine, which would also double the number of ships passing through Tallurutiup Imanga, one of Canada’s largest marine protected areas. And this is all before global warming potentially opens up the Northwest Passage to shipping.

With many of the world’s current busiest shipping channels overlapping with areas where whales or other marine fauna are feeding, giving birth, nursing their young, or travelling to find food, there is a substantial risk of injury or fatality as ships collide with these animals.

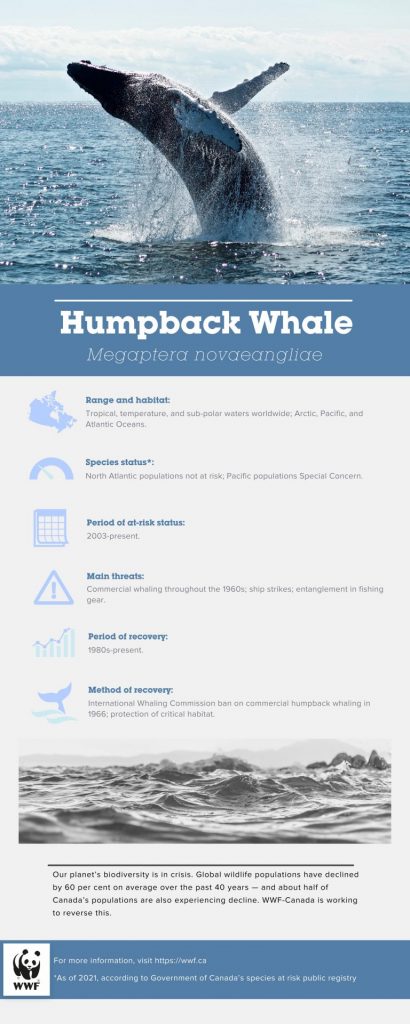

North Atlantic right whales, for example, are considered one of the most endangered large whale species in the world. With less than 400 left, they are classified as endangered under the Species at Risk Act. In 2019, the Marine Animal Response Society (MARS) and Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative investigated the cause of five North Atlantic right whale deaths that occurred in the Gulf of St. Lawrence that summer. The report concluded that four of the five deaths were caused by vessel strikes, some of which were likely shipping vessels.

According to the report released by MARS, 25 right whale deaths over the last five years have occurred in Canadian waters. But attributing the magnitude of right whale fatalities to collisions with shipping vessels is not straightforward. Often, collisions occur offshore and go unnoticed, or there are no trained individuals present during the initial investigation to assist with necropsies (as the evidence of vessel strike is often internal). As a result, the cause of death is often left undetermined.

Tonya Wimmer, Executive Director of the Marine Animal Response Society, explains that as humans, we have little control of where the right whales choose to be. “In the past, people thought, ‘maybe we could scare the whales away’,” she says, “which on one hand is not exactly ethical because [the whales] may need to be in that area — to have a baby, eat, mate, socialize, whatever it is.”

We need to place our efforts on human-centered changes to solve this problem. These changes often come through policy, voluntary measures, or mandatory measures.

After several mass mortality events of right whales in 2015, 2017 and 2019, the Government of Canada began to implement policy changes to reduce the likelihood of shipping vessels encountering these whales, one example being moving shipping lanes near the Shediac Valley.

However, moving shipping lanes is not always a straightforward solution when dealing with mobile animals. “You need to know where the animals are, and the other part of that is that these animals move,” says Wimmer. Right whales travel through different areas every year, “so if you don’t have a dynamic way to deal with the management side of things you might run into problems.”

Wimmer explained that in some areas, it is also impractical to move shipping lanes due to geographical restrictions, or that moving shipping lanes in one area to avoid a species might result in placing the vessels in the direct path of another.

When spatial management and shipping lane alterations are not possible, another way to lower the risk of vessel collisions with whales is by implementing speed restrictions in high-risk areas. In 2017, Transport Canada issued a speed limit of 10 knots or less for boats 20 meters in length or greater within the western Gulf of St. Lawrence with a fine of up to $25,000 for non-compliance. A slower moving vessel would offer more time for animal detection or allow the animal time to move out of harm’s way. Should a strike occur, lower speeds might decrease the probability of the event being fatal.

While speed restrictions have been shown to be somewhat effective, they are an imperfect solution. “Just putting [speed limits] down to ten knots is still not reducing the risk to zero, it’s not even getting close to zero,” says Wimmer. Researchers at Dalhousie University in Halifax suggested in a study that a vessel moving as slowly as 10 knots may still be enough for a fatal collision. Furthermore, smaller shipping vessels less than 20 metres long have been proven to still inflict serious injuries on whales. Yet these smaller vessels are not subject to the same Transport Canada regulations as larger vessels.

While increased attention on right whale conservation measures is certainly a positive step forward, Wimmer’s take is that governments need to be more proactive than reactive. “It took 12 right whales to die for there to be this lightbulb moment…it put a real fire under [the government] to say we need to solve this problem”. And while right whales have moved into the spotlight in terms of conservation (and rightfully so), they are not the only species at risk of fatal ship collisions.

In 2016, the Canadian Government released Canada’s Oceans Protection Plan. The plan focused on three whale species: belugas, southern resident killer whales, and North Atlantic right whales. Wimmer says the plan ignored other species, such as blue whales and fin whales, also at risk from vessel strikes. “The focus was on three whale species, which is bizarre especially from a [government]agency who is supposed to do things from an ecosystem point of view,” she says.

To understand mitigations necessary to protect a species, where they need to be, and if measures are even working, Wimmer says that collection of information and data through performing necropsies is crucial. “With so many humpback, minke whale, fin whale, and even blue whale [deaths] that go uninvestigated, we could potentially be watching these species walk toward the edge of extinction and we don’t have the information to know that it’s happening. We certainly don’t have the information to know how to stop it.”

“We are not always able to go out there and figure out what happened to them,” says Wimmer. Under the Species at Risk Act, when an animal listed under the act dies, it should be investigated. But for this to happen, organizations like MARS require support to reach the animal in time and perform a full necropsy to determine the cause of death. Without doing so, the full extent of this issue, and as a result, how to solve it, will never be known.

While right whales are susceptible to collisions with shipping vessels, they are not the only species we should be focussing on. In addition, the shipping industry is not the only culprit in whale strikes. This issue is complex, focussing on a mobile, somewhat unpredictable species, crossing industry lines and political borders. Solutions will require a proactive, collaborative approach between NGOS like MARS, fish harvesters, and governments.

One such collaboration is an online platform called Navigating Whale Habitat, co-developed by WWF-Canada, the Marine Mammal Observation Network and the St. Lawrence Global Observatory along with government and maritime industry partners. It’s designed to help ship owners and operators safely traverse the Northwest Atlantic, including the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence, by identifying high-risk areas and improving data collection.

“[Management] has to have that conservation side as well, not just for industry, not just to meet international commitments, it has to have that conservation and ecosystem component… there is no silver bullet, but we do need to be more responsible,” says Wimmer.

Alexandra Scaman completed her Masters degree in Environment and Sustainability at Western University. She also holds a Bachelor’s of Science from the University of Windsor with Honours in Environmental Studies, where she concentrated in Resource Management and was actively involved in undergraduate research. Outside of academia, she enjoys hiking, camping, and spending her summers on the beach in Prince Edward Island.

Interview participant contact info

Tonya Wimmer, Executive Director of the Marine Animal Response Society

Transport can image Reference (map) – Protecting North Atlantic right whales from collisions with vessels in the Gulf of St. Lawrence (canada.ca)