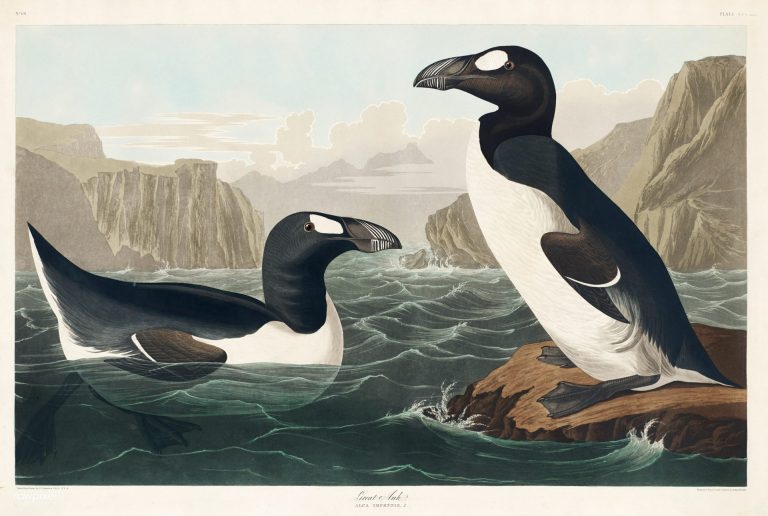

Canada’s eastern shore is much emptier than it used to be. Had you walked the coast of Nova Scotia in the 1800s, where a tumultuous ocean met stubborn granite, you might have seen a flightless bird watching you from the lip of a boulder. It stood about waist height, with a long and jagged bill, its back straight and wings folded neatly against black and white plumage.

This bird, which could navigate the shoreline and rough ocean effortlessly, went by many names; some called it spearbill, a reference to the dagger-like beak extending entire inches past its face. Others called it penguin, the first species ever to carry the name, before it was repurposed for the denizens of Antarctica. In the annals of natural history, it’s called the Great auk, once common on islands and oceanfronts across the North Atlantic, now a stark reminder of nature’s fragility.

The last breeding pair was killed by sailors on the Island of Eldey, off the coast of Iceland, in 1844, a legacy of excessive hunting arriving at its natural conclusion.

Extinction, by definition, is permanent. And in the 1800s, there was no Species at Risk Act (SARA) which could have made the difference for these auks; no opportunity to recognize the lack of data on their health and distribution, putting contemporary naturalists to work.

Let’s pretend for a moment that such a framework existed then: after scouring the North Atlantic, conservationists would have discovered only one colony on the Icelandic Isle of Eldey and proclaimed the species extirpated from Canada, meaning gone from one region but not another. Iceland, then, exercising its own version of SARA, would have assembled experts to “assess” the status of the species. Was it of special concern (three steps from extinction), threatened (two steps from extinction), or endangered (one step from extinction)? Each designation would come with a battery of mandatory conservation initiatives and timelines, perhaps early enough to save the species and protect its only remaining habitat.

When a plant, animal or fungi is on the road to extinction, we call them species at risk, our attempt to quantify and categorize the hemorrhaging of our biosphere. This categorization takes place at many different levels, such as the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Red List, which identifies the most at-risk species globally. Nationally, we have the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), an exceptionally thorough scientific body which debates the finer points of, say, habitat availability for New Brunswick’s cobblestone tiger beetle, before making its recommendations to the Canadian federal government. The Species at Risk Act, overseen by Environment and Climate Change Canada as well as the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, accepts or rejects COSEWIC’s designations after accounting for sociopolitical factors, a consistently controversial filter.