When my Austrian grandma passed away, I found her 20-year-old Dirndl in her wardrobe. Although it was much too big for me, I was emotionally unable to throw it away. Eventually, I decided this Dirndl deserved to be worn again. So, I opened all the seams, divided it into its components and reassembled it. Since it was a very simple garment, I added lace and a border to the hemline, and a hand-stitch to the upper part. Finally, to complete the look, I bought a matching Dirndl blouse.

When my Austrian grandma passed away, I found her 20-year-old Dirndl in her wardrobe. Although it was much too big for me, I was emotionally unable to throw it away. Eventually, I decided this Dirndl deserved to be worn again. So, I opened all the seams, divided it into its components and reassembled it. Since it was a very simple garment, I added lace and a border to the hemline, and a hand-stitch to the upper part. Finally, to complete the look, I bought a matching Dirndl blouse. The first time I wore the outfit, my husband asked, “did you buy a new Dirndl?” By using my grandma’s Dirndl as a resource for a new product, I was participating in a “circular economy” business model, which aims to reduce resources and avoid waste.

In 2013, the average North American consumer purchased 64 garments – about five per month. Clothing consumption has steadily increased over the last 30 years, and is expected to continue increasing due to low prices and fast changing fashion trends. The North American apparel market is expected to continue growing at a rate of about two percent per year, and this growth will require the use of more resources. Continuous population growth will also increase global fibre consumption; global population is expected to exceed 8.5 billion people and global garment production to increase by 63% by 2030. The Global Fashion Agenda report states, “this [economic] model is reaching its physical limits.” The entire industry needs an overhaul for environmental and economic reasons.

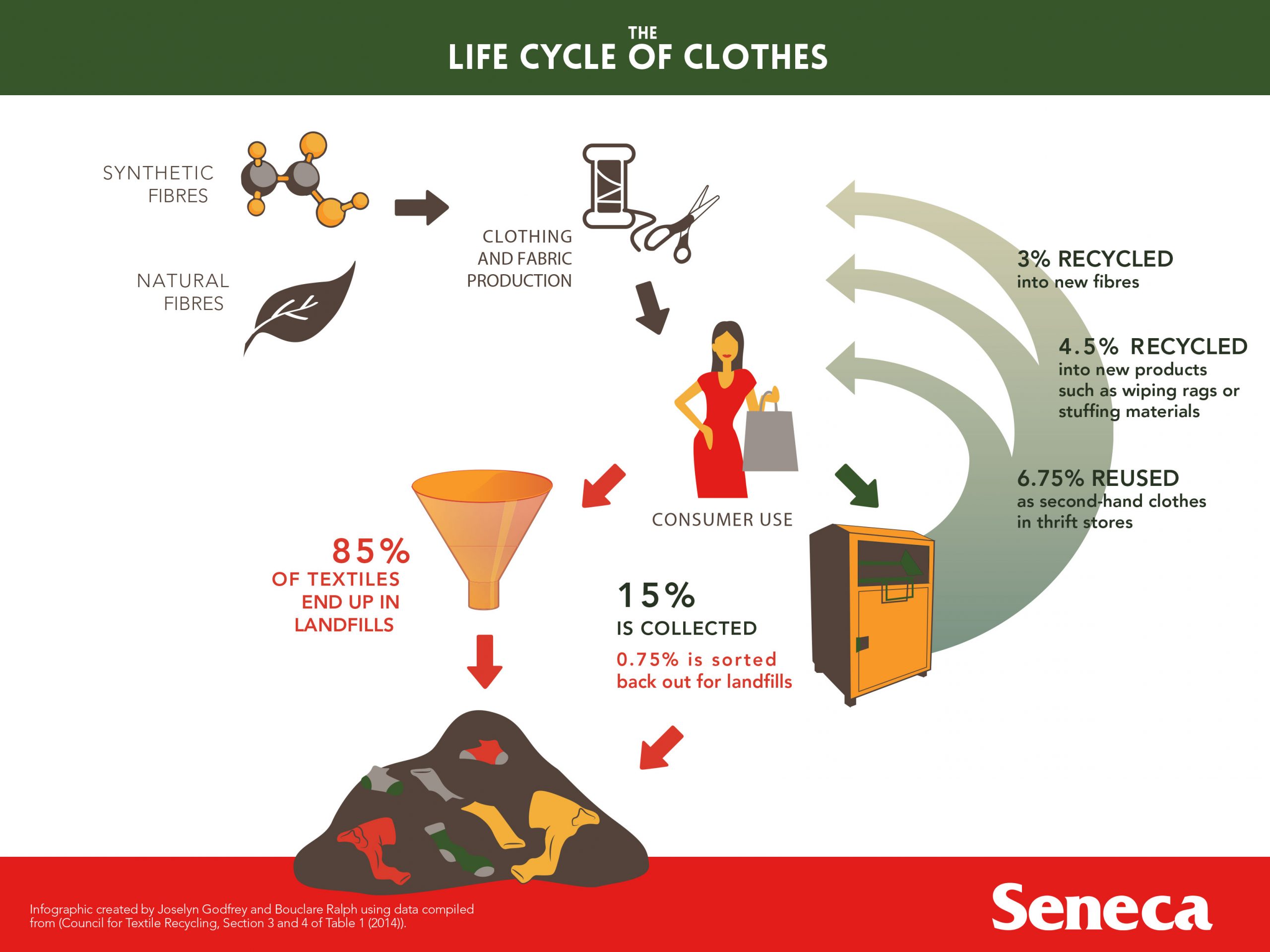

“Fast fashion” or “throw away fashion,” has changed the way we dress and the way we consume. Fashion has become disposable and has ultimately led to more waste. Each year the average consumer disposes 82 pounds of unwanted garments and textiles. While consumption and waste generation has increased, textile recycling has not developed at the same pace. Today, textiles account for approximately 5-10 percent of the waste in North America’s landfills. This estimate is based on waste audits of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the province of Nova Scotia (Jensen, 2012). The rest of post-consumer textiles in North America, 70 pounds per person per year, ends up in the residential waste stream (Council for Textile Recycling, 2014). The common fashion business model today is based on consumers buying, using and disposing of clothes. This linear business model has made the fashion industry the second largest polluter of all industries, just behind the oil industry.

In contrast to the “buy, use and dispose” model, a circular economy keeps material flow in a “closed loop” from an industrial ecology perspective. Walter R. Stahel, an influential sustainability expert and author of the prize-winning paper “The Product-Life Factor”, summarizes the closed loop: “reuse what you can, recycle what cannot be reused, repair what is broken, remanufacture what cannot be repaired”(Stahel, 2016, p. 435). A circular, closed-loop economic approach promotes the “3R” principle of waste reduction – reduce, reuse and recycle – by circulating materials in an endless loop of use.

Cradle-to-cradle design is an approach to design and production that considers the life cycle of a garment from its inception in order to close the production loop. For example, a blouse designed with a cradle-to-cradle approach might be made out of 100 percent polyester fabric, buttons and threads. Using only one material type, rather than several, makes it easier to recycle.

China officially accepted the circular economy as a development strategy in 2009. The country strives for a nationwide implementation of a circular economy on both corporate and social levels. Likewise, the European Union is pushing towards a circular-economy driven by legislation promoting waste reduction and recycling programs.

The effort European brands and retailers are making to “close the loop” is no coincidence or simply voluntary, it is instead a result of the EU’s “take back” legislation, which requires brand owners to be responsible for collecting, recovering and disposing of their products.

While the circular economy concept is promising, several factors have slowed its adoption in Canada, including a lack of strategy in the industrial and government sectors. In Canada, a retailer pays taxes and duties on all imported garments. If a garment goes unsold, retailers have two main options. If the company discards it at a landfill, the import duty is refunded since the garment is considered “unused” and a loss. But if the material is recycled in Canada (“used” according to the Federal Government) the duty is not refunded. In other words, the government actively encourages dumping excess garments instead of recycling them.

Perhaps the greatest impediment to a circular economy in Canada regarding textiles is the lack of textile recycling facilities. Though every garment can be recycled in some way, collection systems and processing facilities are needed to do so. For example, when Nova Scotia began its textile waste initiative, the first challenge was to determine all sources of textile waste. They eventually realized how big the problem was, but didn’t have any solutions. Indeed, though the province proposed banning textiles from landfills in 2015, two years later they have yet to implement their ban.

Designers have opportunities to reduce the resources needed for a textile product itself. This infographic was developed by students from the School of Fashion at Seneca College. “Seneca’s textile diversion program is one way the School of Fashion is involved in several sustainability-focused initiatives,” says Chair Gitte Hansen. “This is part of a larger effort to promote and embed sustainability in the Seneca Culture and the values and learnings we impart to our students.”

What are the solutions?

A circular economic strategy requires the active participation of all stakeholders involved in every aspect of an item’s lifecycle. This includes everyone from design, production and supply chains, distribution channels such as retail and wholesale, to consumption, and then the waste management sector, including municipalities, textile collectors and recyclers. Every stakeholder group has opportunities to help close the lifecycle loop of a garment. Let’s take a look at each of them to consider how they might be implemented.

Design

Every product starts with design. Designers have opportunities to reduce the resources needed for the product itself. For example, fully-fashioned knitting is a process that produces custom pre-shaped pieces of a knitted garment and is therefore virtually waste-free. Every fibre has a different environmental impact, and by carefully considering the life cycle of materials for their products, designers can save significant resources. Generally, the lighter the design, the fewer materials and resources are required. For example, polyester and nylon are strong fibres, making thin and durable material. Products made from these fibres require less material compared to cotton or linen fibres to achieve a comparable degree of durability.

Though many consumers are proud of their cotton and presumably more environmentally friendly reusable shopping bags, bags made of nylon or even polyester require less material for an equally strong bag, and have a lower environmental impact. Shopping bags made from recycled nylon or polyester are even better choice, since they require less energy for the fibres and fewer resources overall. Using recycled fibres for new products is an important step in supporting recycling efforts.

Designers can also put more meaning into their products to give consumers more value and reduce excessive consumption. Garments today are meant to be disposable, or at least replaced by the next fashion cycle. Designed at one place, produced in another and sold elsewhere, these fast-fashion garments leave consumers with mass produced, anonymous products. There is often no relationship between consumer and producer, and no understanding of the amount of work going into a garment. The garments are easy to discard because they mean little to the consumer, but are difficult to recycle because they are soaked in chemicals. Garments must be designed from the start in a more sustainable way by connecting makers and consumers more closely. (A\J covered this idea in Kish and Quilley’s “DIY,” Ecological Economics 43.1)

In the circular economic strategy, every stakeholder group has opportunities to help close the lifecycle loop of the garment

Manufacturing and supply chain

A circular economic strategy seeks harmony between economy, environment and society, with efficiency as the primary aim. Environmental efficiency means achieving the highest degree of value from something. In the past, this may have come at the expense of the environment. A circular economy, however, has a long-term vision of efficiency. What is efficient from a short-term perspective may not necessarily be efficient or expedient over the full life-cycle of the product, brand or environment.

The overriding goal of efficiency in a circular economy is to find ways to reduce resource use by reducing both the volume of fabric materials used in production and the amount of CO2 emissions in transporting these materials. Some of the ways clothing producers have integrated these considerations into their production processes include local sourcing of production and materials, which reduces transportation costs and pollution while respecting the natural ecology of the region.

Fashion designer Peggy Sue, located in Milton, Ontario, has included the search for locally sourced natural and raw material as fundamental to her design and manufacturing choices by partnering with the Upper Canada Fibreshed (UCFS). Based on the idea of a watershed, the fibreshed builds relationships between farmers, artisans, mills, designers and consumers to create a strong local textile economy within a 400 km radius of Toronto.

Retail and distribution channels

When products have a lower price per unit (in other words, can be sold cheaply), many retailers in the fast-fashion industry would rather have excess inventory than risk running out of stock. This practice results in huge amounts of inventory that is never sold, not even through clearance.

One of the most ecological and ethical options to handle this excess inventory is to donate the items for recycling. For example, fashion recycler Debrand Services, based in Delta, BC, offers secure disposal and recycling for unsold clothing merchandise from retailers and industry. Since more than 90 percent of all garments are made offshore, Debrand must convince their client to forfeit the duty refund they would have received by dumping, and on top of this, pay extra for the recycling. Despite these impediments, Debrand is thriving, and lists companies like Lululemon, Columbia or Aritizia as clients.

Consumers

The average garment is worn fewer than seven times before it is disposed, and most women in North America own clothes they have never worn. To benefit their psyches and bank accounts, consumers should focus on buying fewer clothes of higher quality. Moreover, they should look for clothing made of recycled materials or with a more sustainable approach like organic and fair trade or locally made cotton. Companies will change their practices when their customers make different choices about where and on what to spend their money.

If we buy less today, we’ll have fewer clothes to discard tomorrow. Currently, our economic system encourages us to consume more, but we don’t have to accept this. There are so many great opportunities to participate in the circular economy. Buy clothes from second-hand stores, and trade that unworn sweater sitting in your closet at a swap event. Send garments to repair and mending services – most repairs are cheaper than we might assume. Return clothes through company take-back programs. Donate or sell all unwanted clothes rather than dispose. Even underwear and socks can be donated so long as garments are dry, clean and odourless. There are also plenty of clothes sharing and renting programs like Rent frock Repeat, a Toronto-based company that rents out the most beautiful designer outfits to be returned “guilt free” after a single use. You can even rent your daily outfit from Toronto start-up Boro.

We know the steps needed to create a circular economy, now we just need to take them.”

Waste management sector

This sector consists of textile collectors, privately owned companies, charities and municipalities in charge of waste management and textile recyclers.

To close the loop, unwanted garments must not end up in the waste bin, but instead be collected, sorted and diverted for further reuse.

The municipality of Markham, Ontario began a textile diversion program in February 2016 and banned used clothing in their waste stream in April 2017. According to Claudia Marsales, senior waste and environmental manager, the municipality of Markham and its partners have collected more than five and a half million pounds of textile waste. Other leading municipalities of textile diversion include Colchester, Nova Scotia and Aurora, Ontario. Along with Markham, they have instituted post-consumer textile waste diversion programs. But three municipalities in all of Canada are not enough.

The National Zero Waste Council summarizes the Canadian waste policies: “Canada is united in the achievement of zero waste, now and for future generations.” Such an approach can be achieved only in a circular economy, when products are designed to be recirculated into the economy as materials from which new products will be made. Though zero waste master plans for many products exist, textiles remain unaddressed. The National Zero Waste Council itself has yet to take any action towards textile waste diversion.

Although Canada has a well-established textile sorting industry which resells used clothing globally, Canada lacks recycling possibilities for textiles due to a lack of technology and potential end markets for recycled products. It seems that textiles are the forgotten waste.

The promise of a circular economy is hopeful. There have been significant contributions to the development of a circular economy for textiles at local, provincial and industrial levels, however, it has yet to receive the mass scale required to create a sustainable, circular fashion system. Today, only 15 percent of Canada’s unwanted textiles are diverted from the landfill. Of that amount, only three percent is reclaimed into new fibre, less than five percent is recycled into new products and less than seven percent is resold. We know the steps needed to create a circular economy, now we just need to take them.

Sabine Weber worked for nearly 20 years in Europe as product manager/head of design in the fashion industry, and as an international buyer/team leader in retail before she came to Canada She pursued her passion for ethical and sustainable fashion by earning a Master’s degree in Environment and Resource Studies at uWaterloo with a focus in waste management and social marketing. Weber is a PhD student at uW, teaches at Seneca in the fashion program, and is almost always working on projects related to textile waste.