New buildings, new roads and new bridges: In Poland, growth seems to be everywhere. The streets bustle with energy, purpose and the feeling of people striving for a better future – but the country’s need to safeguard its environment on its journey to prosperity is creating challenges Canadians will recognize.

New buildings, new roads and new bridges: In Poland, growth seems to be everywhere. The streets bustle with energy, purpose and the feeling of people striving for a better future – but the country’s need to safeguard its environment on its journey to prosperity is creating challenges Canadians will recognize.

Poland has had a model economic recovery since switching 25 years ago from centrally planned to a market economy, though privatizing inefficient state-owned industries and replacing aging infrastructure required drastic, painful measures. Only 10 years after being accepted into the European Union (EU), Poland has become one of the EU’s key economic players. Its GDP growth has not wavered in the face of the recessions and economic dips that have hit other member states. Yet Poland must still make tangible gains in human and capital productivity to be on par with Western Europe – while meeting the EU’s expectations regarding environmental targets.

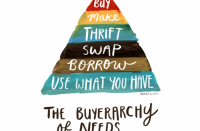

EU-driven peer pressure has led to significant improvements in Poland’s waste and wastewater treatment. The public’s willingness to change its behaviour to achieve waste reduction and water conservation targets is noticeable in public places, hotels and commercial buildings, a number of which are seeking LEED certification.

Polish consumers and businesses alike eagerly adopt environmental innovations, according to the dozen representatives of foreign companies whom I spoke to at POLEKO, Poland’s annual environmental conference, in Poznan in October 2014. Most of the hundreds of companies and organizations gathered there were German, Dutch or Scandinavian, but a growing number of Polish-owned companies are emerging from the Green Technologies Accelerator (GreenEvo), an environmental incubator administered by the Polish Ministry of the Environment.

Polish consumers and businesses alike eagerly adopt environmental innovations.

Prote Technologies is one such homegrown success story. Prote implements micro- and ecosystem-level strategies to address deforestation, fertilizer run-off and algal blooms, which have contaminated Poland’s water systems, threatening to render them unusable for drinking, fishing or recreation.

One of Prote’s water-testing methods is a rudimentary form of bio-indication. Prote’s Symbio system comprises of a group of 10 freshwater mussels, whose natural reaction to sudden changes in contaminant levels is to close their shells. Prote rigs the mussels with wires that detect the widths of the shell openings. “We know there’s a contaminant in the water when the mussel shells close slightly,” explains a Prote spokesperson. “This closing action triggers an alert, causing a water sample to be taken and sent to the lab for testing.” The popular Polish beer company Zywiec has used Symbio for more than a decade to test contaminants in the spring water used in its beer.

The Polish government proudly holds up environmental start-ups like Prote as examples of what its people can achieve. Poland’s highly educated workforce, investment in environmental innovation and numerous incentives for the private sector position it to attract foreign investment to fuel future growth.

Poland’s days of favoured status within the EU may be numbered, however. The country recently went head-to-head with fellow EU members from Western Europe over environmental reduction targets for coal. While original EU member countries are investing heavily in renewable energy like solar and wind, more recent members from Eastern Europe remain far more reliant on coal.Poland has also leveraged its EU membership to great benefit, receiving more EU funds than any member country, contingent upon meeting its EU environmental commitments through 2020. It’s no accident that Poles are aspirational environmentalists.

RELATED: Joe Vipond Explains Why Alberta Doctors Are Working to End Coal-Fired Power

Coal is the source of more than 88 percent of Poland’s electricity. Though its air has among the highest concentrations of particulate matter in Europe – well past acceptable health limits – for many Poles, coal means jobs, energy independence from Russia and economic prosperity. Their conflict between protecting human and environmental health, and maintaining economic stability, is familiar: in Canada, many citizens consider oil and an automobile-enabled lifestyle more essential than curtailing pipeline development through natural habitats.

Coal is the source of more than 88 percent of Poland’s electricity.

Petr Hlobil, a director at the non-profit CEE Bankwatch Network, which monitors international development investments by EU-led funding bodies to ensure public interest is protected in the recipient countries, says, “coal is a big issue in Poland, and elsewhere in Eastern Europe. We see a concentration of investment in coal by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). In some cases, the projects funded by the EU Banks are resulting in inadequate consideration to the local health implications of the investment.”

NGOs like Bankwatch are exploring locally owned and community-driven alternative energy solutions with new and potential EU member countries. “Community-based energy solutions ensure that some of the profits are used locally,” says Hlobil, though local energy solutions are a lower priority for Poles than maintaining their newfound economic stability.

The partisan divide between jobs and environmental targets is a familiar one for Canadians. Poland’s future success – like ours – depends on it safeguarding the health of its citizens and environment as it continues its journey to prosperity.

Natasha Milijasevic is a Toronto-based management consultant whose practice focuses on projects, processes, data, and how organizations can measure these to improve their social impact. Her past research and publications span group psychology to business strategy.

Wife, mother of two and occasionally exhibiting artist, Milijasevic also loves school: she has a BSc, MBA, PhD, and is going back for another one in health care analytics. Her degrees and consulting experience have taught her how to think about complex organizational and technology problems, but the perennials and butterflies in her garden help her to stop thinking about them.