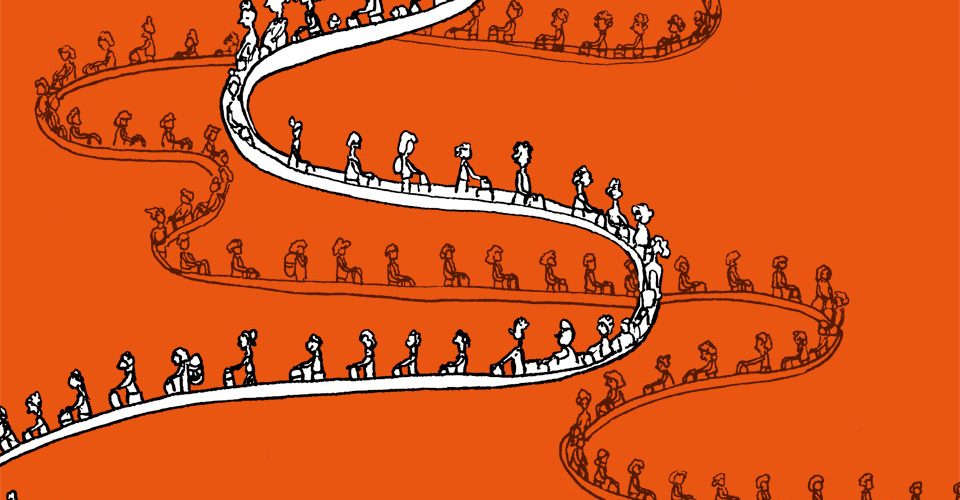

AIRPORTS EVOKE MIXED FEELINGS. Few of us enjoy serpentine lineups, running along moving sidewalks checking our watches, or unpacking our belongings for security personnel. Yet some of the most interesting spaces we’ll meet on our journeys are the airports we rush through.

AIRPORTS EVOKE MIXED FEELINGS. Few of us enjoy serpentine lineups, running along moving sidewalks checking our watches, or unpacking our belongings for security personnel. Yet some of the most interesting spaces we’ll meet on our journeys are the airports we rush through.

From Japan’s Kansai airport built on the ocean, to Jedda’s state-of-the-art terminal for transporting thousands of pilgrims to Mecca, to Denver’s lounges adorned with apocalyptic murals, airports tell us a lot about cultures. They can also reveal a lot about our relationship with nature. Never mind the carbon footprint of flying; from location, to construction, to the people flowing through them, airports drastically change a landscape and the populations, human and wild, that live there.

Runways require enormous swaths of land. The average runway for commercial jets is around three kilometres long, and major airports have up to half a dozen. Denver International, mid-sized as airports go, is twice the size of Manhattan. To accommodate them, forests are felled, farms and wetlands paved, and communities relocated.

Take Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport, whose name means “the golden land.” In the 1970s, the Thai government purchased 3,400 hectares of river floodplain to develop the city’s second major airport. Formerly known as the “Cobra Swamp” (Nong Ngu Hao), this wetland was an important way station along the East Asian migratory bird flyway. It was also home to white-eyed river martin, Siamese Bala shark and other endangered species.

Thailand’s government envisioned the airport as the nucleus for a new economic centre “as big as Singapore.” The imagined aerotropolis has been slow to emerge, but Suvarnabhumi has doubtless been a gold rush for Thailand’s economy as a gateway for commerce, ecotourism and beach getaways.

From location, to construction, to the people flowing through them, airports drastically change a landscape and the populations, human and wild, that live there.

Yet its site on a former wetland continues to haunt Suvarnabhumi. Bird-airplane collisions plague the airport. In 2009, a landing aircraft flew into a flock of painted storks; seven hit the plane, denting the nose-cone and damaging a wing. Thai authorities responded by trying to eliminate birds from the area. Concrete and artificial turf replaced grass. Nearby wetlands were filled in to eliminate avian food sources such as fish and snails. Chemicals and noise were used to deter birds from entering flight paths. The efforts had some success – as far as flight safety is concerned, at least. In 2006, 104 species of birds were found on airport lands. By 2014, the number had dropped to 79.

Exotic animals remain an unhappily familiar sight at Suvarnabhumi, however. The Thai gateway is a hotspot for illegal wildlife smuggling: 11 otters were found alive in a suitcase in 2013. Sadly, Suvarnabhumi isn’t the only air hub that facilitates trafficking of rare species, particularly in regions where their protection is lax. Airport gift shops give rural communities new sales outlets for handcrafts made from local woods, corals or shells – but seldom question the source of those materials.

Expediting tourism to exotic areas can also damage the ecosystems that attract the visitors. The Galapagos Islands saw about 1,000 visitors a year in the 1960s. After the addition of a second airport, the number jumped to 80,000 in the 21st century. After recovering from near extinction in the 1930s, Baltra Island iguanas are now often spotted as road-kill from increased tourist traffic.

Suvarnabhumi \ Anam Ahmed

The upside of “airside”

Airport researchers call all that flat land around runways “airside.” North American airports sprawl over more than 3,300 square kilometres of it – enough to cover half of Ontario’s Algonquin Park. All this airside provides habitat for red-tailed hawks, blue herons, red-winged black birds and killdeer. Stormwater holding ponds attract waterfowl like ducks and geese. Field mice, jackrabbits and woodchucks, drawn to vegetation, attract foxes, coyotes and predatory birds.

While many North American grassland birds are losing habitat to urban fragmentation, airports may be providing alternative habitats. The authors of Wildlife in Airport Environments calculate that as little as 50 hectares of airside grassland may enrich species diversity in developed landscapes. Montreal’s largely abandoned Mirabel airfield has been turned into pasture for 350,000 managed honeybees. Advocates for threatened monarch butterflies point out that milkweed – an essential host for monarch larvae – could flourish around North American runways.

But bird strikes aren’t the only danger to people when wildlife and aviation meet. A few wasps may have brought down Birgenair Flight 301 shortly after take-off from the Dominican Republic in 1996, killing 189 passengers. Investigators concluded that mud-dauber wasps nested in the aircraft’s pitot tubes while it was parked on the tarmac, disabling the air-speed sensors. Unaware of their flight speed, the pilots lost control of their aircraft. (Ground crews are now supposed to cover pitot tubes on aircraft parked for any length of time.)

Anam Ahmed

Symbolic places

The airport terminal is unlike an earlier generation’s train station. Places like New York’s Grand Central Station draw visitors for their neoclassical architecture and accessible commerce. Suburban airports, by contrast, have become what Alistair Gordon describes as “vacuum-sealed” experiences, where passengers are funneled through “super-insulated” concourses (the average one runs nearly half a kilometre in length) into “shadowless holding tanks … oblivious to the outside world.”

This impression is by design. Airports are in the business of selling flying in a time when air travel is fraught with anxiety, inconvenience and climate guilt. Once past security, passengers enter a stateless transit zone. Lounges and cafes offer anonymous diversion on the way to the gates that beckon us to global escapes. Travel-themed ads reinforce the image of the universal globetrotter, with promises like “Your destination just got closer” (Boston Logan), or “We see tomorrow” (Vancouver International).

Nonetheless, airports also serve as symbolic gateways to their host cities or nations. No worries if you only got as far as shopping in Singapore. Before you board your flight at Changi Airport you can still “visit” a range of Malaysian ecosystems that include orchids, cacti, rainforest and butterflies, thanks to its air-conditioned indoor “Nature Trails.” Beyond the airport’s doors, of course, deforestation continues to chew away at the biodiversity of southeast Asia’s actual jungles.

As big countries develop, domestic air travel burgeons. While Brazil is still “a country of few roads,” observes Hugh Pearman, architecture critic for The Sunday Times of London, it has developed “a complex network of internal flights and is building to accommodate them.” Environmentalists may cringe at the thought of rainforest disappearing under taxiways, but Brazil is simply following other countries’ lead.

In 1972, Canada’s federal government expropriated 7,430 hectares of Ontario farmland to create a second major Toronto airport. The purchase turned the hamlet of Altona into a ghost town, removed some of Canada’s best farmland from family ownership, and forced the hasty (and ultimately unnecessary) excavation of a Huron ancestral site. Community resistance stopped the development, and 2,000 hectares in the Rouge River Valley were turned over to the province for parkland. But the rest remained in the federal government’s hands and in 2014, then-finance minister Jim Flaherty announced that it was again available for airport and commercial development.

So the next time you’re catching your breath after the hike from check-in to gate, take a moment to look beyond the UV-filtered glass, past the busy tarmac infield, to the landscape beyond. We’re unlikely to forgo air travel entirely any time soon. But we can work on ways to make its touchdowns and takeoffs less devastating to the environment. We can explore better ways to share airside space with wildlife. And perhaps as travelers, we can recall the impacts that ripple out from the boarding lounge before we book another flight to the far side of the world – or across the province.

You don’t need to hop on a plane to discover yourself. Learn more about the 100-mile Travel Diet at ajmag.ca/TravelDiet.

Visit ajmag.ca/GreenGetaway to learn about other planet-friendly options you can choose to see the world.

Michael Young is a Toronto-based writer and actor.