STANDING ON A RIDGE near Osoyoos in southern British Columbia, we came together to celebrate and protect the rich biological diversity of the Okanagan Valley. Ranchers, teachers, local government officials, children and scientists like myself, we had come to announce the preservation of the Sagebrush Slopes and Sparrow Grassland, more than 1,200 acres of prime grassland.

STANDING ON A RIDGE near Osoyoos in southern British Columbia, we came together to celebrate and protect the rich biological diversity of the Okanagan Valley. Ranchers, teachers, local government officials, children and scientists like myself, we had come to announce the preservation of the Sagebrush Slopes and Sparrow Grassland, more than 1,200 acres of prime grassland.

Grasslands represent less than one per cent of the landscape in BC, yet they provide habitat for a third of the species at risk in the province. The Nature Conservancy of Canada targeted the area for conservation because of 30 species known to be at risk on this land (including Lewis’ woodpeckers, burrowing owls and pallid bats), successfully raising money from the community to match a federal grant.

What had brought us to this point? Not only a concern for the continued decline in the diversity and abundance of species both globally and locally, but a recognition that we must act and we must act now. We knew that we must work together as a community to achieve meaningful protection for species at risk.

Concern for Biodiversity

Our children today live in a world that contains far fewer natural resources than the one into which we were born. Over the past decade, more intact forests have been lost from Canada than from any other country in the world, with Global Forest Watch estimating losses of over two million hectares per year. In the world’s oceans, two-thirds of larger predatory fish such as tuna have been lost due to over-fishing in the last century. Globally, over one in five species of vertebrates and plants are at risk of extinction. While extinction is a natural process, current rates of extinction are estimated to be 1,000-fold higher due to human activities than background rates.

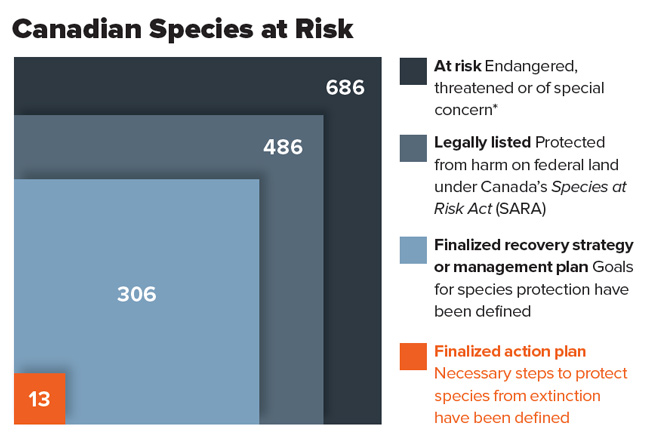

Within Canada, there are approximately 70,000 known species of plants, fungi and animals, with another 35,000 or so yet to be discovered. While we know little about the status of most of these species, 686 are known to be at risk of extinction.

I wish I could report that these species are strongly protected in Canada, but the truth is that protection is spotty at best. Listing of an endangered species under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA) prevents direct harm or killing on federal lands, but federal lands represent only about five per cent of the land base in Canada’s provinces. Furthermore, the habitat needed to protect a species (“critical habitat”) has not been specified for the majority of species at risk in Canada. Until it is identified, destroying critical habitat remains legal, even on federal land.

SARA hasn’t provided meaningful protection for the majority of species at risk in Canada. The problem isn’t so much the law, but a failure to uphold it. For example, only three of the 67 species identified as at risk since 2011 have been listed under SARA, even though a listing decision is required within nine months. Two hundred Canadian species at risk are waiting simply to have their status legally recognized (see “Canadian Species at Risk” above).

The lack of effective action to protect our most vulnerable species has been widely recognized, including in a number of legal decisions. In the words of the Auditor General of Canada:

“Environment Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Parks Canada have not met their legal requirements for establishing recovery strategies, action plans, and management plans under the Species at Risk Act.”

– Neil Maxwell (2013), Office of the Auditor General of Canada

The elephant in the room with SARA is that it only applies on federal lands. At the provincial and territorial level, there is a patchwork of protection for Canada’s at-risk biodiversity. Some provinces have lead the way with strong programs to protect vulnerable species. For example, Ontario, under its Endangered Species Act, automatically follows the recommendations of its independent scientific committee about which species are at risk. More importantly, once listed, there are broad restrictions against harming the species or its habitat. Sadly, other regions, notably Alberta, British Columbia, Saskatchewan and the Yukon, lack laws dedicated to protecting species at risk. The lack of strong legislation and effective action has contributed to ongoing declines in biodiversity, as concluded in a recent BC audit:

“[D]espite the BC government’s decades-long objective to conserve biodiversity, and commitments made on the national and international stage, the biological diversity of our province is in decline. This audit found that government is not doing enough to address this loss of biodiversity.”

– John Doyle (2013), Office of theAuditor General of British Columbia

We Must Act Now

We must turn the tide. Over the past few decades, the situation for Canadian species has worsened. A recent study found that the status of species at risk in Canada has declined for more species (115) than improved (52), as a result of piecemeal efforts to protect species at risk and their critical habitats. Bird populations have declined by 12 per cent, on average, since 1970, with over 40 per cent declines in some groups (grassland birds, aerial insectivores and shorebirds).

Waiting isn’t the right strategy. Habitats do not necessarily recover if we’ve altered them too much. Ecosystems are complex and reducing one species can alter interactions among the remaining species in a manner that prevents the system from bouncing back. For example, cod remain at extremely low abundances after a 20-year moratorium on their catch. Climate change is exacerbating the issue by causing mismatches between species adapted to a particular habitat and the conditions now found in that habitat. Furthermore, landscapes altered by development, clear-cutting and other human activities block species from responding to climate changes by moving to more suitable areas.

Collaborating for the Future

Saving species at risk is possible, especially when governments and communities work together.

A promising path forward is to protect natural lands and waters through reserves. If we make a mistake and grant a development permit for a project that does more environmental harm than expected or set allowable catch levels too high for fisheries, then species within reserves are protected from our errors. Habitat reserves also provide a source of biodiversity to supply surrounding unprotected areas, such as fish migrating from marine protected areas and pollinating bees from land reserves. Habitat reserves can also be targeted to maximize protection of species known to be at risk, such as in the grasslands of southern Okanagan, focusing protection on hotspots of Canadian biodiversity.

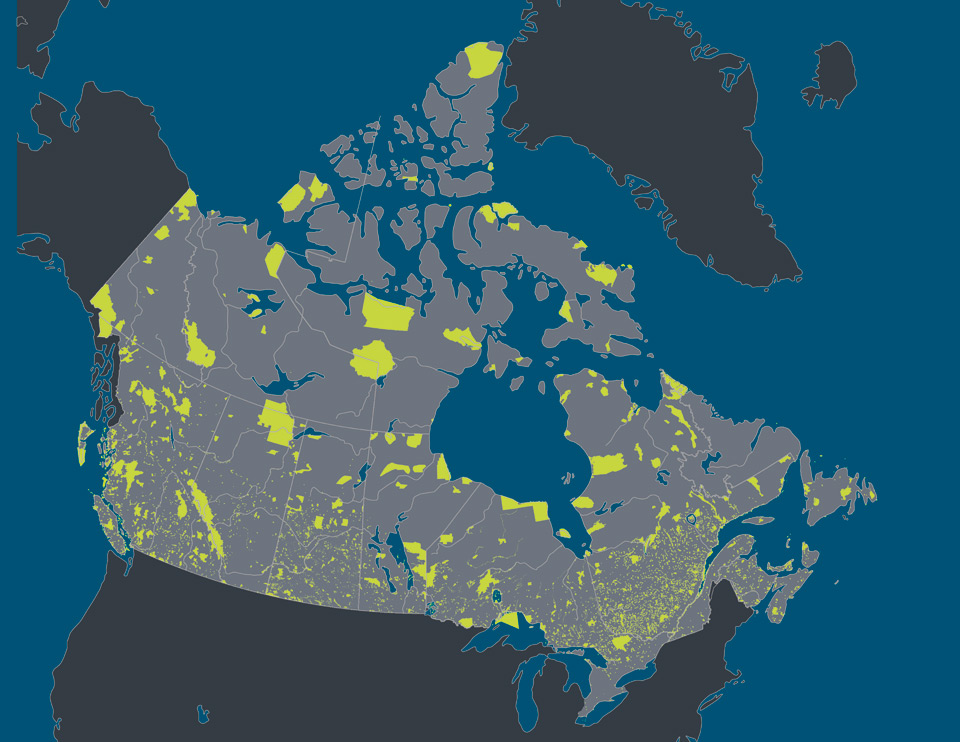

Canada’s Patchwork of Protected Areas

Currently, only 1.04 million square kilometers (10.4 per cent) of Canadian land are protected. Most of this land falls within national parks (54.7 per cent), wilderness areas (33.2 per cent), natural monuments (6.9 per cent) or protected areas with sustainably used natural resources (5.0 per cent).

Map Source: Conservation Areas Reporting and Tracking System (CARTS), via Canadian Council on Ecological Areas (CCEA)

Canada, as one of the signatories of the 2010 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), set out to preserve at least 10 per cent of marine areas and 17 per cent of terrestrial areas and inland waters by 2020. We currently protect less than one per cent of Canadian marine areas and about 10 per cent of Canadian land. Furthermore, many of our protected lands are disconnected, and they are often far from the ecosystems and species at greatest risk.

If we wish to halt the decline in Canadian biodiversity, we must be willing to put our time, our resources and our votes on the line to let government know that protecting Canadian nature matters to us. Our governments will follow suit if we make it politically impossible not to do so.

That is why the community stood together on the ridge near Osoyoos, to take a stand for the conservation of land that we knew needed protection. Land trusts, like the Nature Conservancy of Canada and the Nature Trust of British Columbia, prioritize the areas that are most valuable to protect – not only the lands with the greatest species diversity, but also those that provide wildlife corridors and critical ecosystem services such as clean water. Land trusts also do something else: They work to build teams of supporters (landowners and volunteers) to build communities that care about the land being conserved. Such community support makes true habitat protection possible.

In support of habitat conservation, the Harper government recently budgeted $252-million for the National Conservation Plan. I applaud this action, but the amount falls short. Even if all the money went for land purchases, the funds would purchase less than 0.1 per cent of Canadian land. We cannot meet our 17 per cent CBD target in this piecemeal fashion. Furthermore, marine reserves cannot be purchased – they must be legislated. Crown land and marine areas must be protected, and these require provincial and federal commitment to bolster the current system of national parks, wilderness areas and marine protected areas.

We must push forward – together – to achieve meaningful protection of Canada’s biodiversity and preserve a large fraction of our lands and waters in a manner that is mindful of where species are most at risk. At the same time, we must act to reduce excessive risk to all species that call Canada home, such as reducing harmful pollutants and tackling the spread of invasive organisms. We must join voices to call for more effective protection of species and their habitats in Canada. As a country highly dependent on natural resources, protecting natural habitat is critical for a sustainable future economy. Habitat protection is also a promise to our children to save some of Canada, relatively untouched, for their discoveries and for their inspiration, so that they too can stand on ridge tops and be awed by Canada’s natural diversity.

Looking for more on biodiversity? Read about why Canada is failing to protect species at risk and the court case against the Ontario government, accused of violating the Endangered Species Act.

Sarah Otto is a professor in the Department of Zoology and director of the Biodiversity Research Centre at the University of British Columbia.