In the early hours of July 26, 2010, Sue Connolly bundled her children into the car and drove to the local daycare in Marshall, Michigan, like every other weekday. But on this morning, something was not quite right. “There was a very strong odor in the air. It just took your breath away. My eyes and throat were burning.” Connolly would soon discover that the largest and most expensive on-land oil spill in US history had occurred the night before – right in the middle of her community.

In the early hours of July 26, 2010, Sue Connolly bundled her children into the car and drove to the local daycare in Marshall, Michigan, like every other weekday. But on this morning, something was not quite right. “There was a very strong odor in the air. It just took your breath away. My eyes and throat were burning.” Connolly would soon discover that the largest and most expensive on-land oil spill in US history had occurred the night before – right in the middle of her community. Like many residents of this sleepy town of 7,000 in the southwestern part of the state, Connolly had no idea that millions of litres of oil were flowing beneath her feet on a daily basis. Today, you would be hard pressed to find anyone in Marshall who is not acutely aware both of the presence of pipelines and the potential danger they represent.

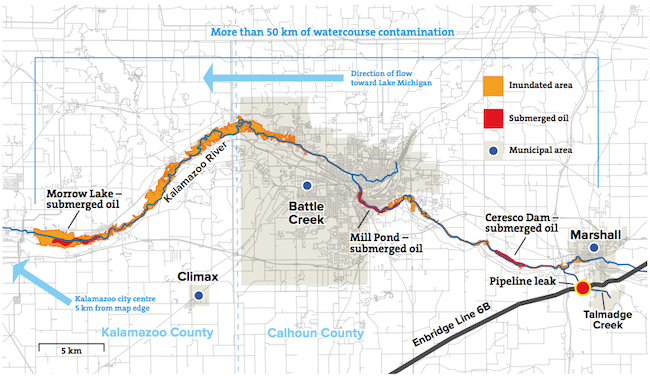

All told, nearly 4 million litres of heavy crude spilled from a two-metre gash in a below-ground pipeline known as Line 6B, blackening a three-kilometer stretch of Talmadge Creek and almost 60 km of the Kalamazoo River, an important regional waterway. Most of the tainted stretch of the river between Marshall and the city of Kalamazoo remained closed to the public for two years, and about 150 families from Marshall were permanently evacuated from their homes. Line 6B is operated by Enbridge Energy Partners, the US branch of Calgary-based Enbridge Inc., and it runs roughly 450 km from Indiana to Sarnia, Ontario. It’s part of the company’s 3,000- km Lakehead system of pipelines, which transports bitumen oil from the tar sands of northern Alberta to major refining centers in the Great Lakes region, the Midwest and Ontario.

Three and a half years later, Enbridge has spent more than $1-billion cleaning up the river, and their work is not yet done. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently ordered the company to return to dredge a 65-km span of the Kalamazoo where remains of the heavy Canadian oil have collected. While most of the crude has been recovered, remnants remain in the floodplains, on riverbanks and in the sediment at the bottom of the river.

With billions of dollars in new pipeline projects and expansions in the works across North America, companies like Enbridge are eager to allay the fears of an increasingly jittery public about the risks of moving oil through pipelines. Hoping to understand what exactly happened there in 2010, I joined a learning expedition to Michigan in May 2013, organized by the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources. What I discovered was a community still coping with the tragedy, a community whose story should be a cautionary tale for us all.

On the evening of July 25, 2010, the 0.65-centimetre-thick wall of Line 6B’s 76-centimetre-wide carbon steel pipe ruptured near Talmadge Creek, just over a kilometre away from the nearest pump station. This caused a high priority alarm to sound in the Enbridge central control room in Edmonton. Multiple other alarms went off in the ensuing minutes, indicating pressure problems and discrepancies between the volume of oil entering and exiting the pipe. Control room operators ignored these warnings, believing that a large bubble had formed between batches of crude – not a cause for serious concern.

State of panic

Back in Marshall, oil was pouring into wetlands and Talmadge Creek throughout the night like water spewing from a decapitated fire hydrant. By the next morning, the community was in a state of panic. The river level was already high due to days of heavy rains. Thick, oily muck was now oozing over the banks, coating tree trunks and soil, and sloshing into the flood plains. Michigan Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) staff arrived on the scene quickly, finding muskrats, turtles and other small animals coated in oily goo. First responders included firefighters and local utilities who were responding to 911 calls and resident complaints about an unusual odor. Once the source was detected, authorities realized the spill would soon reach the Kalamazoo River, which eventually feeds into Lake Michigan, the source of drinking water for millions of people.

“I remember a cop car driving by with a loud speaker ordering everyone in the area to evacuate due to the benzene levels,” recalls Beth Wallace, a community outreach coordinator with the National Wildlife Federation. “At the time we were not aware of how much of a risk it actually was. Nobody knew how to respond. It was unprecedented.”

Some 2,400 km away, alarms continued in Enbridge’s Edmonton control room throughout the morning, yet operators still disagreed on whether there was even a problem. Twice they pumped even more crude into the ruptured pipeline in an effort to solve the perceived “bubble problem,” all the while ignoring the repeated alarms. It wasn’t until the source of the leak was confirmed that an employee from a Michigan utility company called Enbridge directly and the pumps were finally turned off, 17 hours after the spill started.

First responders in Marshall were woefully unprepared for a spill of this magnitude. “When we got a call that there was an oil spill,” says Jay Wesley of the MDNR, “we expected to see an overturned truck or something like that. Half the river was black. My staff had never been trained for this type of event.”

And because Enbridge was not required to disclose to federal and local officials the contents of the pipeline, it wasn’t until a week later that responders even knew what kind of oil they were dealing with.

Horizontal Damage from the Kalamazoo River Oil Spill

The spill was much worse than it would have been at a drier time of the year. Spilled bitumen contaminated large swathes of the floodplain (indicated in orange) in addition to the riverbed.

Map data adapted from: openstreetmap.org, insideclimatenews.org and Enbridge Energy’s “Line 6b Incident – Conceptual Site Model 2013.” Diagram by nik harron.

Health impacts of crude oil exposure won’t be known for years

This was no ordinary crude. Tar sands oil is a thick and viscous substance with the consistency of peanut butter. It has to be combined with a cocktail of toxic chemicals to produce something called diluted bitumen, or “dilbit,” in order for it to flow through pipes. Scientists don’t fully understand how some of these chemicals affect humans and other organisms when released into the environment, as there has been relatively little long-term research into the impacts of oil spills. We do know, however, that these diluents usually include benzene, a known carcinogen that can affect human health at low concentrations over short periods of time.

By the time Sue Connolly picked up her kids from daycare that fateful afternoon, “it was apparent that the children and staff were already having symptoms from the chemicals in the air, including headaches, lethargy and diarrhea. That first night my son was throwing up and within three days, my daughter developed a strange rash. Other children had similar symptoms.”

About 320 people in the area reported symptoms consistent with crude oil exposure and 145 were treated, but some experts say it will be years before the full human health and ecological impacts of the spill are known. Alaskan marine toxicologist Riki Ott has been studying the health impacts of oil spills for years, particularly related to the Exxon Valdez disaster in Alaska in 1989. She says recent medical research has linked exposure to oil spill fumes with a host of symptoms and illnesses in humans and animals, including cancer, liver and kidney disease, fetal abnormalities and miscarriages. Ott predicts the Michigan spill will eventually trigger illnesses in some residents that their bodies haven’t expressed yet. “Very few people are looking at the public health implications of oil disasters. If the full human health costs [of these accidents] were known, it would change our energy future immediately.”

Sue Connolly wonders whether her children will experience fertility problems because of the accident when they want to start their own families. “What if people in our community are being diagnosed with cancer and other health issues in the future? How will we know if it’s connected to this exposure?”

Three years later

Looking out onto Talmadge Creek only 5 km from where the pipeline burst, I had a hard time believing that the entire area was blanketed with a layer of sludge only three years prior. “It was totally devastating to see it in the first weeks and months after the spill because there was visible oil everywhere,” says MDNR’s Jay Wesley. “Now when you canoe it you probably will hardly even tell. And the fish communities are still there, the bugs are coming back, the turtles are still there. So it does show that it is a resilient system and it does heal itself eventually.”

Although the river looks better, Wesley says it will be many more years before the agency can measure the full impact on fish and other animals’ reproductive cycles. And EPA officials estimate there are still roughly 700,000 litres of oil on the river bottom.

“Pervasive organizational failures”

An investigation into the incident by the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) cited “pervasive organizational failures at Enbridge” that included deficient management, inadequate training, insufficient pipeline inspections and an ineffective spill response. NTSB chair Deborah Herman famously compared Enbridge’s handling of the spill to “Keystone Kops,” in reference to incompetent police in silent films.

The NTSB found that corrosion of Line 6B was the underlying cause of the catastrophic breach, exacerbated by a flaw in the outside coating of the 40-yearold pipe. Fatigue cracks and corrosion defects had grown and coalesced under polyethylene tape coating that had peeled off the outside of the pipe, eventually producing a substantial crack in the steel. Yet records from the US Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration reveal that the defect that led to the rupture was detected at least three times before the spill occurred, and Enbridge had done nothing to address the problem.

Enbridge acknowledges that mistakes were made (which is different from “we made mistakes”) and that they have made many improvements to their operations. “This was the largest spill in the 60-year history of Enbridge,” company spokesperson Jason Manshum told me. “Our goal has been and always will be zero incidents. Clearly we’re not there yet, but we’re putting all the pieces in place to minimize the risk.”

The difference with dilbit

In the aftermath of the spill, there was much debate about the inherent risks of transporting diluted bitumen. Enbridge and the US Association of Oil Pipelines (AOP) claim the rupture of Line 6B had nothing to do with the product being transported. According to John Stoody, AOP’s director of government and public relations, “diluted bitumen is a heavy crude that is similar to others like Venezuela or California or Mexico. We’ve been transporting it through pipelines for over 40 years.” A recent report by the US National Academy of Sciences seemed to agree with this assessment, concluding that dilbit is “no more likely to cause corrosion than other crude oils.”

To prove this to journalists at the Enbridge offices near Marshall, Manshum passed around a small vial full of dilbit to demonstrate that it sounds just like water when shaken and is no less viscous than other crudes. Yet environmental groups continue to have their doubts about its safety. A 2011 study by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), Sierra Club and the Pipeline Safety Trust claims that in the Alberta pipeline system, which transports a “high proportion” of dilbit, there were 16 times more spills than in the US system. As was the case in Kalamazoo, 40-year-old pipelines that were originally designed for different products are now being used to transport dilbit, which has high sand and sulphur content and is transported at higher temperatures and pressures than conventional oils. Incidentally, this is precisely the plan for the proposed Line 9 Energy East project that would see the flow reversed in an existing 37-year-old pipeline from Sarnia to Montreal without any significant design modifications to accommodate dilbit.

In addition to dilbit’s corrosive properties inside the pipe, the other important revelation from Kalamazoo concerns the way dilbit behaves when it gets outside. The Michigan accident proved that dilbit eventually sinks in water. This fact was one of the most challenging aspects of the cleanup operation, far more difficult than cleaning up oil that is floating. “We’re coming into the third year of intensive cleanup activity, and now we’re looking at very intrusive and expensive dredging to try to get it out of the worst places where it’s accumulated,” says Stephen Hamilton, an ecology professor at Michigan State University and the independent science adviser to the cleanup.

Manshum doesn’t deny that some leaked oil ended up at the bottom of the river, but he attributes this to “turbulent water and high river flows. The oil adhered itself to debris and that’s when it started to sink.”

Jeff Short, a respected US environmental chemist, has found that dilbit does sink in both fresh and marine waters under certain conditions. Environment Canada has reached a similar conclusion and, based on lessons learned in Michigan, the US EPA has urged that special standards be set for tar sands crude because of the additional risks it poses when it spills. Short’s research found that dilbit would sink within 25 hours at low water temperatures and high wind speeds. These are precisely the conditions often found in Kitimat Arm on the central BC coast, where giant oil tankers would congregate should the controversial Northern Gateway pipeline from Alberta to the Pacific be approved.

Photo from David Kenyon, Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

Enbridge’s Line 6B leaked along Michigan’s Talmadge Creek and Kalamazoo River, impacting several species in the watershed, including painted turtles and the herons that hunt in and around the affected floodplain.

Pipeline accidents will continue to happen

Line 6B through Michigan is now back in operation, although Enbridge is currently in the process of replacing it with a 91.4-cmdiameter pipe (the old line is 76.2 cm) and an increased flow capacity of 500,000 barrels per day (up from 250,000). Given Enbridge’s spotty safety record, many local residents are worried. Marshall homeowner Dave Gallagher, whose house lies directly in the path of 6B, wonders whether the new pipeline will be safe despite Enbridge’s claims. “They’re curving the new pipeline around our house,” says Gallagher. “Pumping oil at that kind of pressure, what’s that going to do to the pipe? The heat that’s generated from these pipes melts the snow in our backyard in the wintertime. There’s no company that can say there will never be a leak. Past experience shows these pipes eventually leak.”

Yet Enbridge’s Manshum insists that the latest advancements in pipeline technologies have made transporting oil in any form safer than ever. To demonstrate, he showed us a sample of the latest materials his company uses to construct their new pipelines. He said the coating is epoxy-bonded with a wall thickness of 1.7 cm for pipes that go under highways and water bodies, and 0.95 cm for the rest, whereas existing lines are typically 0.6 cm thick. “The new coating should not allow any moisture between the tape and steel. We also have more sensors and leak detection capability.”

After the horrifying accident in Lac-Mégantic, Québec, in which a runaway train carrying crude oil derailed, exploded and killed 47 people in July 2013, an expansion of the presumed safer alternative – pipelines – seemed reasonable. Yet this response overlooks one of the central lessons of the Kalamazoo disaster: that pipeline accidents will continue to happen. Over the last 20 years, there have been an average of 250 pipeline incidents each year in the US and one rupture every 16 years on average for every 1,000 km of pipeline in Canada. Across all its operations, Enbridge alone has had at least 804 spills between 1999 and 2010, releasing roughly 19 million litres of hydrocarbons. This amounts to approximately half of the amount of oil spilled by the Exxon Valdez tanker after it struck a rock in Prince William Sound, Alaska, in 1988.

“I would love to assure you that there will be no leaks again, but I can’t tell you that,” says Manshum. “We’re dealing with mechanical equipment and there is always the chance of mechanical failure.”

As conventional fossil fuel supplies are exhausted and climate change intensifies, humanity appears to be entering a new and more dangerous energy era. Many mistakes – both human errors and equipment failures – led to and exacerbated the tragedy in Michigan. The Kalamazoo accident showed us that although communities and natural systems can eventually recover, the longterm health and ecological consequences of oil spills are still not well understood. Michigan environmental officials now say it could be years before they are ready to issue a final verdict on the damage done to the Kalamazoo River ecosystem.

“What I think is the really important thing about Kalamazoo is that we are in the midst of a really big fundamental change in the type of fuel we are getting in this country,” says NRDC spokesperson Josh Mogerman. “The industry in Canada plans to triple production by 2030, and folks who are concerned about climate issues and safety issues are concerned about these production numbers. That’s part of the reason why you’ve seen such an uproar over the proposed Keystone XL pipeline.”

It’s also important to remember that the Line 6B rupture occurred just minutes from Enbridge’s maintenance facility in Marshall, so some equipment – such as vacuum trucks, skimmers, underflow dams and oil booms – was close at hand. The town is also close to the cities of Battle Creek and Kalamazoo, so more resources – emergency response technicians, other spill containment and control equipment – were readily available.

By comparison, Enbridge’s Northern Gateway pipeline would run through remote and rugged wilderness areas (as well as important salmon habitat), where conditions such as deep snow, avalanche hazards, heavy rain or high water flows could make response much less effective.

In its much-anticipated report on the Northern Gateway proposal released in December, Canada’s National Energy Board Joint Review Panel recommended that the project be approved provided that 209 conditions are met. The panel concluded that the pipeline is in the “Canadian public interest” and that the potential for adverse environmental impacts on local communities and ecosystems is outweighed by the expected economic benefits for Canada as a whole.

Related: Indirect Impacts of Pipelines Should Be Included in Assessments

Three years after the Kalamazoo spill, Susan Connolly is still struggling to get answers from Enbridge and local officials about the impacts of the accident. She says county and state governments have refused to conduct a long-term health study and she worries about the future well-being of her family and her community. “We want people to know what happened here and we’re going to keep fighting – we are not going away,” she says. “It’s owed to this community but also to the nation because there are so many other towns that will be impacted by pipelines. They have a right to know and to see what’s going to happen to them too. It’s not a matter of if there will be another spill, but when.”

Get the bigger picture of where and how much oil moves through North America. Check out our interactive map of current and proposed major crude oil and dilbit pipelines, including direction, volume and recent major spills.

Mark Brooks is a journalist, broadcaster and environmental educator. Follow him on Twitter: @earthgaugeCA.